The National Express

Urgency and the incomplete legacy of the last Labour government

Since taking office just about four months ago, the new National government has been making energetic use of urgency to begin implementing its agenda. This has sparked some debate, with government critics complaining about the perceived haste with which legislation is being pushed through parliament. We shouldn’t dismiss these concerns out of hand, but it’s also worth noting that there is some important context missing from a lot of the commentary.

Before we get to that, it’s worth going over the basics.

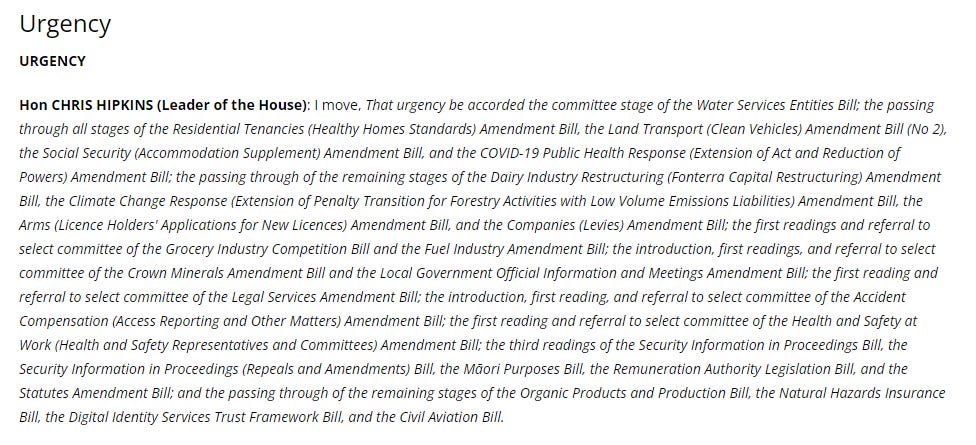

Urgency is a procedural tool that allows parliament to expedite the legislative process. Under normal circumstances, the passage of a bill involves several stages of discussion, debate and review spread out over a period of time. Urgency condenses this. It enables the government to introduce a bill and debate it immediately, bypassing the usual intermediate stages and waiting periods that allows members of parliament to read and form an opinion on the proposed legislation.

In essence, urgency is a mechanism designed to fast-track legislation.

The use of urgency is not without its potential pitfalls.

Urgency is not ideal for every circumstance. When it comes to creating new legal regimes or establishing new institutions, for example, the risks associated with urgency can be quite pronounced. Those things require more careful deliberation and scrutiny to ensure the proposed laws or institutions are robust, fair and are likely to serve their intended purpose.

Rushing that kind legislation involves a heightened risk of unintended consequences. Potential issues with the proposal may not be fully explored or addressed, for example. In these cases, it’s quite common for laws to be refined and improved on the way through. The usual process exists for a reason.

When it is more forgivable.

It’s not quite as worrying when a new government uses urgency to effectively abort complex new laws and institutions before they take effect. And when repeal formed part of the governing party’s election manifestos, urgency may sometimes be needed to give effect to the democratic mandate of the governing coalition. In those cases, urgency can be desirable or even desirable to prevent the entrenchment of policies or institutions that are misaligned with the government's stated priorities.

Three Waters is a classic example.

The Three Waters Reform in New Zealand, conceived by the previous government, aimed to overhaul the nation's water services through the establishment of a small number of mega-bureaucracies. These would take provision of local services from local hands and concentrate power in the hands of functionally unaccountable entities whose members would be appointed through a process almost Byzantine in its complexity.

The reform was deeply unpopular beyond the bubble of Labour supporters and all three parties in the new government campaigned against it and on the rapid repeal of the associated legislation.